Imperium Romanum 211 AD: Map of the Roman Empire

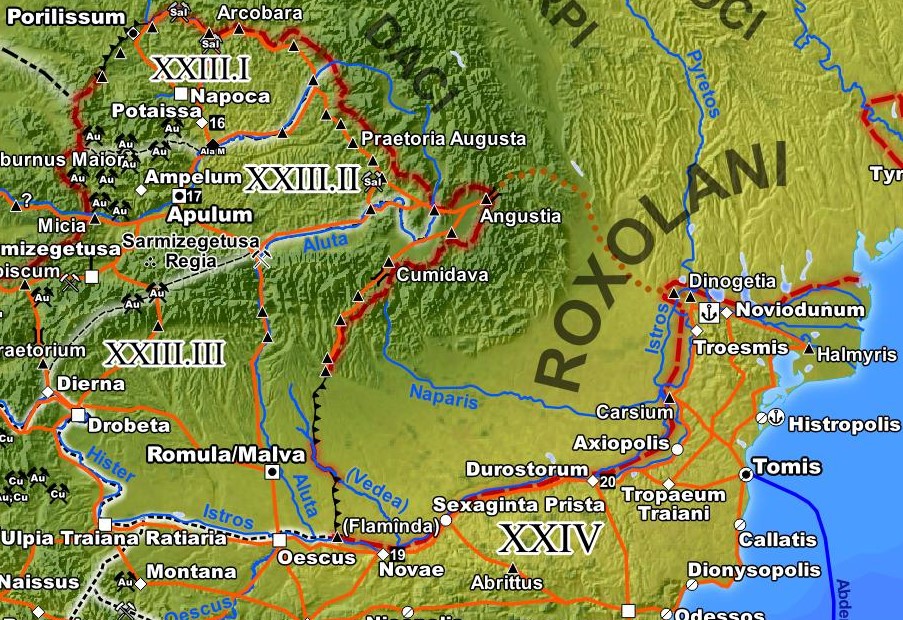

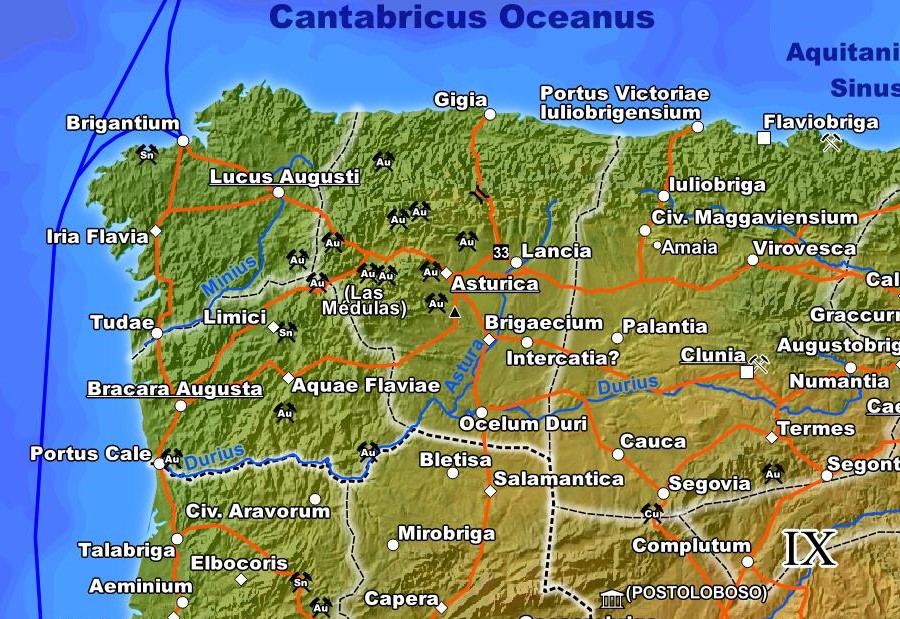

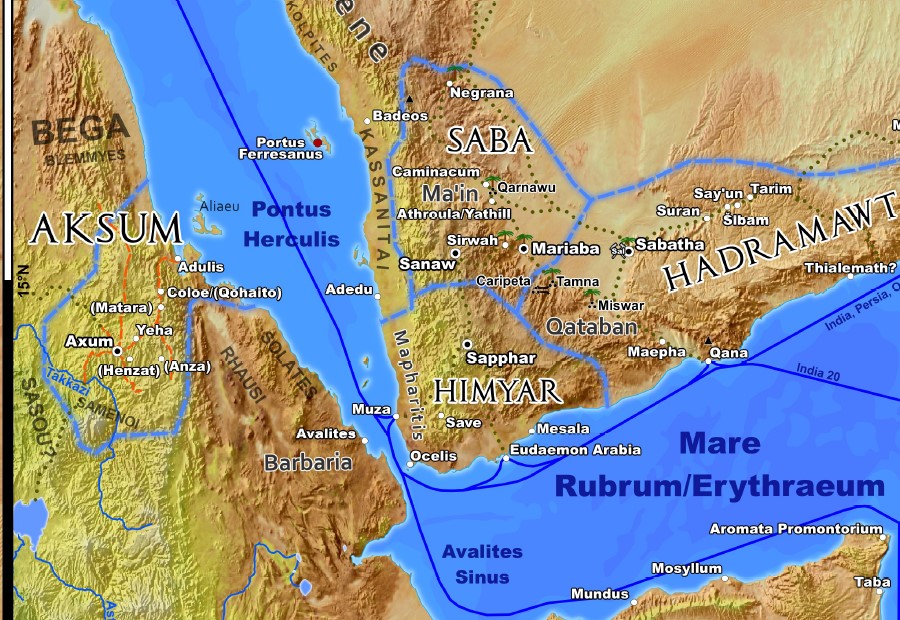

The product of many years of research and a life long passion: A highly detailed, up to date map of the entire Roman Empire from Lower Nubia to the Antonine Wall, with surrounding territories, in the final years of the reign of Septimius Severus, about 211 CE.

The first version of this map was originally published by Sardis Verlag in spring 2014 and later heavily updated for the second edition releases in 2016 (folded map) and 2017 (laminated paper rolled up), The World of Ancient Rome. In 2021 an improved fourth version was released.

Features

- Format: DIN A0 (118,9 x 84,1 cm) or DIN A1 (84,1 x 59,4 cm),

- Scale 1:4.500.000 (DIN A0) or 1:6.000.000 (DIN A1),

- Legend in English, German, French and Italian,

- Geodata modified to correctly portray the Roman World.

States and Settlements

- The Imperium Romanum and its provinces in 211 CE,

- All surrounding client states and independent states,

- More than 120 non-urbanized, "Barbarian" peoples in the vicinity of the Roman Empire,

- More than 1100 Roman cities, distinguished by their respective legal categories,

- More than 110 cities and settlements beyond the borders of the Empire.

Infrastructure

- Roman road network totaling more than 120.000 km,

- Caravan, transhumance and trade routes,

- Major sea routes, including traveling times in the Mediterranean Basin,

- Exporting quarries as well as mining areas for precious and non-ferrous metals.

Military

- The headquarters of all 33 active legions,

- Garrisons of all Alae Milliariae and guard units,

- 28 main and auxiliary bases of the praetorian and provincial fleets,

- More than 150 selected forts,

- Linear barriers, such as Hadrian's Wall and the Limes Germanicus.

HD prints of this map can be purchased from my online store:

All images are from the newest edition Imperium Romanum 211 AD (2021)

All places are now accessible, all are well known, all open to commerce; most pleasant farms have obliterated all traces of what were once dreary and dangerous wastes; cultivated fields have subdued forests; flocks and herds have expelled wild beasts; sandy deserts are sown; rocks are planted; marshes are drained; and where once were hardly solitary cottages, there are now large cities. No longer are (savage) islands dreaded, nor their rocky shores feared; everywhere are houses, and inhabitants, and settled government, and civilized life. What most frequently meets our view (and occasions complaint), is our teeming population: our numbers are burdensome to the world, which can hardly supply us from its natural elements; our wants grow more and more keen, and our complaints more bitter in all mouths, whilst Nature fails in affording us her usual sustenance.

Tertullian (ca. 150 – 220 n. Chr.) De anima, XXX

Commentary - The Roman Empire and its Neighbours

It was always intended that the map should depict the Roman Empire at the apex of its power, prosperity and territorial reach. This restricts the time scope in question to somewhere between the Flavian dynasty and the beginning of the Crisis of the Third Century. In the end, the decision was made to select the reign of Septimius Severus, at the end of that period.

Unlike the territories conquered by Trajan during his Parthian war, the provinces of northern Mesopotamia (created by Septimius Severus) were held in the Empire for more than 160 years. Taken in conjunction with the continuous expansion into the periphery of the Sahara Desert, these conquests give the Roman Empire its largest sustained territorial extent. Simultaneously, this map shows the world of the discontinuing Principate in its final form, before the deep political, economical and religious upheavals of the Third Century.

The map shows the Mediterranean from an Earth orbit perspective. To achieve this effect, the background was composed from landclass and bathymetry data, which was then combined with a shaded relief. Most of the geodata comes from the Natural Earth Project [1], while the shaded relief was calculated using SRTM-based digital elevation data [2]. An equidistant cylindrical projection, centered on a latitude of 40°N, i.e., the center of the Mediterranean, was used. In places where the topography has changed significantly, especially along the coastlines, the geodata was corrected to reflect the ancient topography. The road network is based on the Itinerarium Antonini but was significantly extended for the map.

Cities

Most space in the map is given to the cities, which in Severan times still were the mostly autonomous base units of the Empire. Regional differences in the organization of cities are indicated by the city categories: In the Greek and Hellenized East we find a dense network of cities that were mostly organized in the tradition of the Greek Polis. Civitates and their territories in the Celtic northwestern provinces were oriented on the boundaries of conquered Celtic tribes, leading to larger units of territory. Smaller, newer units could be found in the parts of Agri Decumates to the left of the Rhine. In Egypt, the Romans, just as the Ptolemies before them, took over the existing administrative infrastructure and the nomes, which in part had already existed for thousands of years. The Latinized remainder of the Empire followed the Italian model. Cities that were either founded as Roman colonies or later elevated to that status can be found in all parts of the Empire.

The Latin term "Civitas", which literally means citizenry, is a generic term that may be used for all kinds of autonomous communities, including colonies and independent states. On the map, in contrast, the Civitas symbol is only used for the main settlements of the aforementioned mentioned larger administrative units.

The category of non-autonomous settlements on the map includes notable Vici [3] that were part of a larger administrative unit without being the main settlement in that unit, and Canabae, cities that grew around forts and were subordinates to the military. Both types of settlements could attain a respectable size and surpass proper cities in population.

Also marked on the map are notable sanctuaries which, unlike most holy sites, were located further away from any major settlements. In some cases, the accompanying settlement had been abandoned. One example of this is the island sanctuary of Delos. Once a prosperous free port, Delos lost this function during the Pax Romana and did not recover from the devastation of the Mithridatic Wars.

Sites in Southern Arabia are usually marked with the local name, as used in Antiquity, as well as the one recorded by Greco-Roman geographers. A question mark next to the name indicates that the assignment of the name to this particular site is still uncertain. Names in brackets are modern names for sites that, as of 2014, could not be identified with a historical name.

Borders

Most of the outer borders of the Roman Empire are well-defined through rivers or fortifications. However, for boundary sections where this is not the case, known outposts are connected with lines as a "de facto" border on the map. The statement of Bowersock, that „Just as the Romans did not have provincial boundaries within the waters of the Mediterranean, they were not likely to have defined clear boundaries in the wastes of the great Syrian desert“ holds true for the boundaries through deserts. In these regions, it was attempted to denote the area under direct military control, so far as it is indicated by inscription finds or similar evidence. One example case of this is the bend in the border line through the Sahara desert west of Dimmidi that was included to take into account CIL VIII 21567 at Agueneb and two possible forts at El Khadra and El Bayadh.

Both the eastern and the southern borders have so far not been as intensely researched as the borders within Europe. The emphasis of archaeological work in the southern and eastern regions has been on large urban centers. Forts often have not been investigated through excavations, making their dating and the question of precursor structures uncertain.

Forts

At its peak, the Imperial Roman Army encompassed around 400 alae and auxiliary cohorts, which were distributed over a much larger number of forts, primarily along the borders of the Empire. Of these, only the ones that are essential in understanding the border regions have been included in the map. Another goal of marking these forts was to contrast the staged defense system of the Dacian provinces with the linear nature of the rest of the northern border. In addition, it was attempted to represent the very unequal density of forts that mirrors the non-uniform distribution of troops over the Empire. For instance, while 50.000 - 60.000 troops were stationed in the north of the Danube section of Dacia alone, the entire boundary of Africa, between Sala at the Atlantic and Egypt, was secured with a mere 35.000 troops.

Just as the Legionary fortresses, the garrisons of the special Alae Milliariae are also represented by their own icon on the map. The rare Alae Milliariae were double strength elite cavalry regiments, commanded by equestrian prefects in an extraordinary fourth military position of their cursus honorum.

Mines and Quarries

The map also denotes mines of precious and non-ferrous metals. Most mines were Imperial property and thus contributed significantly to the state treasury. Others, especially iron mines, were so numerous that they produced almost exclusively to fulfill local demand. Regarding quarries, all sites that exported regionally or super-regionally were marked on the map. Again, most quarries were Imperial property, which meant that their products were used for Imperial (but also private) construction projects in the entire Empire.

Roman Territories

Arabia and the Red Sea

There is now some certainty on the southern border of the Roman province of Arabia. A Latin inscription found in Hegra in 2003 proves that this former center of the Nabataean Kingdom was firmly

integrated into the Roman province. When also taking into account inscription finds of Roman soldiers in the territory of the former kingdom, it now becomes clear the Nabataean Kingdom was, in

its entirety, annexed in 106 CE. The precise location of the Imperial boundary, coinciding with one of the main entry points of the Incense Route, was located approximately 20 km south of Hegra,

close to the present-day oasis al-'Ula (in antiquity: Dedan), as is indicated by graffiti of Roman soldiers (including Benificiarii) found there.

Inscriptions demonstrate that the Dumata oasis, located deeply within the desert, belonged to the Nabataean realm of influence. In Severan times, roman troops based in the fort at Qasr al-Azraq

patrolled the Wadi Sirhan. This Wadi connected Dumata to the provincial capital Bostra, an important trade route and attack vector to the urbanized core of the province. In the oasis itself a

ceremonial altar, erected by a centurio of Legio III Cyrenaica based in Bostra, was found, which can be dated to the reign of Septimius Severus, proving the imperial army was in control of

Dumata.

The status of the old oasis city of Tayma in Roman times is unclear. Excavations show that it remained an urban center and that it belonged to the Nabataean Kingdom. Taking into consideration the fate of other Nabataean properties, it is only reasonable to assume Roman dominance, as is the case on the map.

The Roman base on the Farasan Islands (lat. Portus Ferresanus) has been verified through inscriptions for the year 144 CE and for the reign of Trajan. Since the installations could so far not be excavated, there is no clarity on whether or not the base was in use in the year 211 CE, nor on how long it existed. The fact that the base was in use for at least a few decades, thus surviving various changes in leadership, and the fact that the islands had their own prefecture in 144 CE, indicate a certain permanence of the installations.

Archaeological evidence from the harbor cities of Egypt show no decrease in activity before the crisis of the third century. To the contrary, the Roman Empire continually extended its regional power in the Orient (projected through bases) after the successful Parthian wars of Lucius Verus and Septimius Severus. As an example, there is the aforementioned inscription from Severian times in Dumata that shows trade routes and military access vectors being important drivers of imperial policy. In addition, more recent excavations in Myos Hormos and Berenice repeatedly produced evidence of a continued presence of Roman Naval units on the Red Sea. Because the Empire considered southern Arabia to be in its realm of influence, with the corresponding diplomatic relations, there must also have been credible options for military intervention. A base on the Farasan islands would have been extremely useful in this regard, which fuels speculation about predecessors and additional bases. All these considerations, together with the desire to visualize the extent of Roman influence, led to the inclusion of Portus Feresanus in the map.

New archaeological finds fuel the old discussion on whether a separate classis Maris Rubri existed or if the ships were subordinate to the fleet in Alexandria. In any case, there must have been a so far unidentified naval base on the east coast of Egypt. Being the seat of the prefect in charge of the region, Berenice seems the most likely candidate. There is some hope that these questions will be answered in the near future, through the continuing investigations in Berenice and Myos Hormos, as well as the evaluation of existing written evidence.

Traveling Times in the Red Sea and Beyond

All times noted on the map are the actual travel times for the corresponding route. Given the wind system of the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, the travel times along a multi-station route may deviate drastically, which can be misleading [4].

Ships had to leave Egypt in summer so that they could cross the Red Sea using the predominant northerly winds of this season. In the Gulf of Aden, they would then encounter the Southwest Monsoon, which allowed to continue towards India, but made a change of course on the Horn of Africa (Aromata Promontorium), so as to travel in a south-western direction along the East African coast, impossible. Doing so only became possible from around November, when the Northeast Monsoon begins. Likewise, the ships had to wait for 8 months in Raphta for the return of the Southwest Monsoon. Back in Egypt, another 6 months had to pass before the next journey could be started in the following July. With the then common rigging (just as with more modern rigging), travel against strong Monsoon winds was practically impossible.

Mesopotamia

The development of administrative structures in the new trans-Euphratic territories during the time of Septimius Severus cannot be unambiguously reconstructed based on present-day knowledge. This is especially true for the province of Osrhoene (as evidenced by inscriptions) that most likely was put in place already in 195 CE, after the first Parthian War of Septimius Severus. The map follows the conventional wisdom that it existed as an independent province.

However, it is not unlikely that Osrhoene was a sub-province adjunct to Syria Coele, subordinate to the governor there. In this case, its territory would be smaller than shown here, without Rhesaina and the remaining Habur area. After 205 CE, Osrhoene was de facto unified with Mesopotamia and was administered from Nisibis. The commonly accepted date for this is the year 212 or 213, when the client kingdom of Regnum Abgari around Edessa was annexed. Nonetheless, an earlier date, for instance during the reorganization of border defenses in the last years of the reign of Septimius Severus, remains possible.

Regarding the Regnum Abgari, a residual kingdom still attributed to the former King of Osrhoene, Abgar VIII., no precise borders, except at one place, are known. It is usually assumed that this territorial entity was from its inception limited to the city of Edessa and its immediate surroundings.

The city Amida was already raised to the rank of Colonia during Severan times. This also could already have been ordered by Septimius Severus himself, or equally likely by one of his successors.

Surrounding Territories

Aksum and Southern Arabia

At same point between the very late 2nd and the first decades of the third century Aksumite troops crossed the narrow stretch of sea between Adulis and southern Arabia to launch an invasion of Himyar. They enjoyed some initial success, apparently Aksum controlled the coastal plain for several decades and could, in concert with allied local chiefdoms, launch attacks against the inland centers from there. It wasn’t until the later decades of the 3rd century that the invaders could finally be dispelled. By the 4th century rulers of Aksum could, now anachronistically, claim to be kings of Himyar, Raydan, Saba and Salhan as part of their royal titles. However, unlike the later 6th century Aksumite intervention in southern Arabia, this earlier episode is only poorly understood and all details are still a matter of debate. No complete account has survived and evidence is mainly limited to contemporary local epigraphy. Thus other than depicted on my map it may very well be possible that Aksum already held some southern Arabian possessions in 211 AD.

Germania

Reconstructing the situation in Germania at the beginning of the third century posed a problem. Lacking literary evidence from the cultures in question, modern researchers are completely dependent on writings of Roman and Greek authors living far away. While the source base is relatively acceptable for the first century due to original authors such as the historian Tacitus and the Geographers Strabo and Pliny the elder, literary evidence becomes scarce during the time of the Adoptive Emperors and the Severans. For instance, the Geography of Claudios Ptolemaios, dating from the second century, is problematic as evidence since his sources are unknown and seem to dating from a large interval of time.

The dynamic changes in power balance, dependency relations and settlement patterns apparent from these works of writing cannot be clearly retraced for the 100 years that follow. Just as in the Roman realm, Germania experienced massive upheavals during the third century, such as the migration of the Goths to the black sea or the formation of large meta-tribes such as the Franks or the Alemanni. The ethnogenesis of the latter tribe is a controversial topic of present-day research, which also affects this map.

Alemanni

Currently, there are two competing models for the formation of the Alemanni. On the one hand, it is assumed that they originate in Suebian Tribes (or parts thereof), such as the Hermunduri and Semnones, which supposedly migrated to the river Main area shortly after the Marcomannic Wars. According to this theory, this new, militarily powerful union directly adjacent to Roman territory pushed Emperor Caracalla towards a proactive campaign in 213 CE. It follows that the Alemanni would later have been instrumental in the fall of the Limes Germanicus in 260 CE, and would have settled in the former Agri Decumates territory, the area between Limes, Rhine and Danube (Grid D2 to E3 of the map).

The second theory, which is preferred in contemporary research within Germany, assumes a haphazard abandonment of the Limes Germanicus over time, as key troop concentrations were withdrawn to other hot spots during the chaos of the third century. This would have allowed the Suebian (and various other Germanic groups) to settle in the now accessible former Agri Decumates territory. Under this hypothesis, the Alemanni (whose first definite evidence of existence dates to a Panegyricus from 289 CE [5]) would have formed there, within what was once the Roman realm.

A key factor for the plausibility of this scenario is the validity of references to the Alemanni in various Roman reports from the first half of the third century. Particularly relevant are the

two contemporary authors Asinius Quadratus and Cassius Dio, the latter of which writes about the campaign in 213 CE, thus supplying an alternate first notification of existence. However, their

works for this period are only available via later summaries and quotations in Byzantine sources. The interpretation of the people against which Caracalla campaigned as Alemanni in the writings

of Cassius Dio is controversial, because their name appears in three different variants throughout the various fragments, some of which deviate strongly from the standard Latin spelling.

I used the first hypothesis for this map, since I consider the arguments for [6] the veracity of these writings to be stronger. Accordingly, the bulk of the Semnones, who settled between Elbe and

Oder in the area around the Havel and the Spree during the first and second centuries, are already shifted towards the south-west and the Roman border on the map.

Cotini

Another special case is the population that is described as “Cotini” or “Gotini” in Roman sources and has been given the name “Kotiner” in the German literature. These people are likely identical to the archaeologically identified Púchov culture (in the later phase), which had its center in present day Slovakia [7]. Many of the properties ascribed to the Cotini, such as the settlement area, their practice of iron mining and processing, their culturally Celtic traits, and their political dependency on the nearby Quadi, correspond to evidence in the archaeological record of the Púchov culture.

The Púchov culture settlements were abandoned in the late second or early third century. In the known fragments of the history by Cassius Dio (whose contents range until 229 CE), they are described as having been eradicated later, sometime after the Marcomannic wars [8]. Unfortunately, the segments of his work concerning this period have not been preserved. Two inscriptions from the city of Rome dating to the reigns of Severus Alexander [9] and Decius [10] speak of Cotini from the province of Pannonia Inferior [11]. It is assumed that some time at the end of the Marcomannic wars, probably around 180 CE, the remainders of the Cotini populace were resettled to this province, which had been depopulated by war and the Antonine plague. Whether a part of the populace stayed behind, or if the source area was uninhabited for the next decades is unknown. Considering the general uncertainties, I decided to also mark the Cotini at their ancestral location, since the map is supposed to give an overview of the last 135 years of the principate.

Saxones

Similar conditions apply to the Saxones. For them too, the veracity of the first mention by Ptolemaios in the second century is in question, and their name is not recorded correctly in all manuscripts. However, since the Saxones do not appear in any source that is relevant for the time scope of this map, and since they make an appearance as a regional power only in at the turn of the third and fourth centuries, I left them out of this map. If inserted into the map, they would be located east of the Chaucii in the general area of the mouth of the Elbe.

Hibernia

Only few written sources from the Roman realm exist for the Ireland of antiquity. The depiction in this map is based largely on Ireland and the Classical World by P. Freeman, in which the author has united these sources with the archaeological evidence.

A series of Roman coins from the late first to early fourth century and various valuables indicate that the neolithic burial mound of Brú na Bóinne/Newgrange had regional religious significance.

Oasis Cultures and Trans-Saharan Trade

Since the 1990s, after decades of neglect, archaeological research fortunately resumed the investigation of Saharan cultures, which allowed an extraordinary improvement of our knowledge of the region to take place. Of special note is the work of the Italian research mission to the Tadrart Acacus mountains and its surrounding oases (near present day Ghat [12]) led by Mario Liverani and the achievements of the Fazzan project (later: Desert Migrations Project) in central-Libyan Fazzan led by David Mattingly [13]. Both regions are considered to be part of the Garamantian kingdom, whose core territory in antiquity was the Wadi al-Ajal with the capital Garama (present day Jerma). Some doubts, however, remain regarding the area surrounding Ghat.

Compared with research on the ancient Mediterranean, research on the ancient Sahara realm is overall still in its infancy. For instance, the Kufra oases [14] and their surroundings belong to the least explored sites among all presented here.

Regarding both of the two main questions relevant for this map, i.e. the existence of continuous trade in the pre-Islamic Sahara and the existence of an organized state structure for the Garamantes, the investigating archaeologists have converged on confirmation [15]. Both had been strongly doubted or even disregarded in the past [16]. While in earlier research the focus was firmly on trans-Saharan trade towards the Roman cities of Africa (not unlike the better documented medieval trade), newer results show that there were population centers within the desert capable of generating significant imports and exports even in antiquity. Thus, the trade relations between these centers also have to be taken into consideration. With regard to the importance of this trade to the Roman world, it has to be noted that, at the time, the North-African provinces of the Empire already had hundredfold the population of the Garamantian realm (with the entire Roman Empire having thousandfold the population). Exports and imports that were important for the economic development of the Fezzan were therefore never comparable in importance to the trade with the East and Africa that took place via the Red Sea and the Caravan cities of Syria and Arabia. However, they did still contribute to the blossoming of the coastal metropoles of Tripolitania.

In addition to the archaeological record of trade goods, there are some ceramics finds from the Roman era along the Abu Ballas Trail [17] and some Berber-Libyan inscriptions in the Selima Oasis[18] proving that the Sahara was also crossed in all directions away from the main routes by mobile groups.

Differences in the degree of research activity can also be noted in the used and marked paths between the oasis groups. While the routes of antiquity in the deserts west and east of the Nile in Egypt are well-documented through archaeological prospection, the pathways in the central Sahara region can often only be extrapolated indirectly via the distribution of trade goods and the natural conditions, such as water sources.

Footnotes:

[1] http://www.naturalearthdata.com

[2] SRTM30 Dataset with 1 km resolution. Source: U.S. Geological Survey, http://www.usgs.gov

[3] The Latin term Vicus originally designated a quarter or suburb of a larger city, in our time the meaning was expanded to include seperate settlements that legally belonged to their larger city state.

[4] See L. Casson, Rome's Trade with the East: The Sea Voyage to Africa and India, Transactions of the American Philological Association 110 (1980) 21-36.

[5] An overview over this thesis and supporting literature is given e.g. by W. Pohl: "Die Germanen"

[6] As shown in Bruno Bleckmann: "Die Alamannen im 3. Jahrhundert: althistorische Bemerkungen zur Ersterwähnung und zur Ethnogenese"

[7] K. Pieta: "Die Púchov Kultur".

[8] Dio. 72.12.3

[9] 222 to 235 CE.

[10] 249 to 251 CE.

[11] CIL 06, 32542 and CIL 06, 32557, ..ex provincia Pannonia inferiore cives Cotini..

[12] Grid D8 of the map

[13] Grid E8 and F8 of the map

[14] Grid G8 of the map

[15] The recent survey article WILSON 2012: "Saharan trade in the Roman period", for spezific regions for example MATTINGLY 2013a: "The first towns in the central Sahara", MORI 2010: "Archaeological Research in the Oasis of Fewet and the Rediscovery of the Garamantes", or for classical Siwa KUHLMANN 2007: "Das Ammoneion – ein ägyptisches Orakel in der libyschen Wüste".

[16] For example SWANSONS 1971: "Myth of Trans-Saharan Trade during the Roman Era"

[17] Grid H8 to G9 of the map, HENDRICKX 2013

[18] Grid A8, Ancilliary map Aethiopia-Kush, PICHLER 2005

Bibliography - Imperium Romanum 211 AD

The literature consulted by me when making the Roman Empire map. For better readability, the list of sources is separated by topic into sections. We begin with a list of more general topics, then continue with four geographical subdivisions: Africa, the Near East, Northwestern Europe and finally Eastern Europe including Asia Minor and the Danubian provinces.

Primary Sources

- Arrian (b. 85–90, d. after 145/146 CE): Periplus Ponti Euxini

- Cassius Dio (b. ca. 163 - d. after 229 CE): Historia Romana

- Isidorus Characenus (after 26 BCE.): Mansiones Parthicae

- Unknown Author, ca. mid 1. century CE: Periplus Maris Erythraei

- Pliny the Elder (b. 24 - d. 79 CE.): Historia Naturalis

- Strabo (b. 63 BCE. - d. after 23 CE): Geographica

- Tacitus (b. 58 - d. ca. 120 CE): Germania

General

- BECHERT 1999: T. Bechert (ed.), Die Provinzen des Römischen Reiches: Einführung und Überblick, Phillip von Zabern (1999)

- BOWMAN 2000: A. K. Bowman, P. Garnsey, University of Cambridge, D. Rathbone (eds.), The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 11. The High Empire, AD 70–192, Cambridge University Press (2000).

- ENCIR: E. Yarshater (ed.) et Al., Encyclopaedia Iranica, iranicaonline.org.

- FISCHER 2012: T. Fischer, Die Armee der Caesaren, Friedrich Pustet (2012).

- HANSON 2016: J. W. Hanson, An Urban Geography of the Roman World, 100 BC to AD 300, Archaeopress Roman Archaeology 18 (2016).

- KLEE 2010: M. Klee, Lebensadern des Imperiums – Strassen im Römischen Weltreich, Theiss (2010).

- LEPELLEY 2001: C. Lepelley, Rom und das Reich in der Hohen Kaiserzeit 44 v. Chr. - 260 n. Chr., Band 2 Die Regionen des Reiches, K.G. Sauer (2001).

- LÖHBERG 2006: B. Löhberg, Das Itinerarium provinciarum Antonini Augusti, Frank & Timme, Berlin (2006).

- MILLER 1916: K. Miller, Itineraria Romana römische Reisewege an der Hand der Tabula Peutingeriana, Unveränd. Nachdr. [d. Ausg.] 1916, Bregenz: G. Husslein, (1988).

- PFERDEHIRT 2012: B. Pferdehirt, M. Scholz (Hrsg.), Bürgerrecht und Krise Die Constitutio Antoniniana 212 n. Chr. und ihre innenpolitischen Folgen, RGZM, Verlag Schnell & Steiner (2012).

- PLEIADES: B. Turner, T. Elliott et. Al., Pleiades - A community-built gazetteer and graph of ancient places, pleiades.stoa.org.

- ROHDE 2016: D. Rohde, Dorothea, M. Sommer, Wirtschaft, Geschichte in Quellen - Antike, wbg Academic (2016).

- RUSSEL 2013: B. J. Russell, Gazetteer of Stone Quarries in the Roman World. Version 1.0., Accessed (3.2014): stone_quarries_database.

- STILLWELL 1976: R. Stillwell, W. L. MacDonald, L. William, M. H. McAlister, The Princeton encyclopedia of classical sites, N.J. Princeton University Press (1976).

- TALBERT 2000: R.J.A. Talbert (ed.), Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World, Princeton University Press (2000).

- TAVO, Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients, Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag (1975-1993).

- WBG 2024: M. Blömer, A. Lichtenberger (eds.), Erhaben und den Göttern nahe - "Heilige Berge" der Antike, wbg Philipp von Zabern, Verlag Herder (2024).

- WITTKE 2007: Anne-Maria Wittke, Eckart Olshausen, Richard Szydlak, Der neue Pauly. Historischer Atlas der antiken Welt, Metzler (2007).

Geodata

- Shaded relief calculated from SRTM30 dataset. Source: U.S. Geological Survey, usgs.gov.

- Original coastlines, bathymetry and landclass: naturalearthdata.com

Searoutes

- ARNAUD 2007: P. Arnaud, Diocletian's Prices Edict: the prices of seaborne transport and the average duration of maritime travel , JRA 20 (2007), 321-336.

- CASSON 1951: L. Casson, Speed Under Sail of Ancient Ships, Transactions of the American Philological Association Vol. 82 (1951), 136 – 148.

- CASSON 1980: L. Casson, Rome's Trade with the East: The Sea Voyage to Africa and India, Transactions of the American Philological Association 110 (1980), 21-36.

- CASSON 1989: L. Casson, The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary, Princeton University Press (1989).

- CASSON 1995: L. Casson, Ships and Seamanship in the ancient world, Johns Hopkins University Press (1995).

- WEITERMEYER 2009: C. Weitemeyer, H. Döhler, Traces of Roman Offshore Navigation on Skerki Bank (Strait of Sicily), The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (2009) 38.2: 254–280.

Africa

- ALEXANDER 1988: J. Alexander, The Saharan divide in the Nile Valley: evidence from Qasr Ibrim, The African Archaeological Review 6 (1988), 73-90.

- BARATTE 2012: F. Baratte, Die Römer in Tunesien und Lybien – Nordafrika in Römischer Zeit, Philipp von Zabern (2012).

- BLUE 2007: L. Blue, Locating the Harbour: Myos Hormos/Quseir al-Qadim: a Roman and Islamic Port on the Red Sea Coast of Egypt, The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (2007) 36.2: 265–281.

- BOHEC 2013: Y. Le Bohec, Histoire de l'Afrique romaine : 146 avant J-C - 439 après J-C, Editions A & J Picard (2013).

- BREYER 2012: F. Breyer, Das Königreich Aksum. Geschichte und Archäologie Abessiniens in der Spätantike, Philipp von Zabern (2012).

- CASSON 1989: L. Casson, The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary, Princeton University Press (1989).

- CHERRY 1998: D. Cherry, Frontier and Society in Roman North Africa, Oxford University Press (1998).

- EDWARDS 1998: D. N. Edwards, Meroe and the Sudanic Kingdoms, The Journal of African History 39 No. 2 (1998), 175-193.

- EGER 2013: J. Eger, Ancient Traffic Routes in the Sudanese Western Desert - An Archaeological Remote Sensing Project, in Neubauer, Trinks, Salisbury & Einwögerer (eds.), Archaeological Prospection. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference – Vienna. May 29th - June 2nd 2013, Verl. der Österr. Akad. d. Wiss (2013), 127-128.

- FLAUX 2017: C. Flaux, M. El-Assal, C. Shaalan, N. Marriner, C. Morhange, M. Torab, J.-Ph. Goiran, J.-Y. Empereur, Geoarchaeology of Portus Mareoticus: Ancient Alexandria's lake harbour (Nile Delta, Egypt), Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 13 (2017), 669–681.

- GARBECHT 1992: G. Garbrecht, H. Jaritz, Neue Ergebnisse zu altägyptischen Wasserbauten im Fayum, in Antike Welt Band. 23,4 (1992), 238–254.

- GOODCHILD 1952: R. G. Goodchild, Arae Philaenorum and Automalax, Papers of the British School at Rome Vol. 20 (1952) , 94-110.

- GOODCHILD 1953: R. G. Goodchild, The Roman and Byzantine Limes in Cyrenaica, The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 43, (1953), 65-76.

- HARRELL 2009: J.A. Harrell, P. Storemyr, Ancient Egyptian quarries-an illustrated overview, in N. Abu-Jaber, E. G. Bloxam, P. Degryse, T. Heldal, QuarryScapes: ancient stone quarry landscapes in the Eastern Mediterranean, Geological Survey of Norway Special Publication 12 (2009), 7-50.

- HARRIS 1897: Walter B. Harris, The Roman Roads of Morocco, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 10, No. 3 (1897), 300-303.

- HELCK 1974: W. Helck, Die altägyptischen Gaue, Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients, Beihefte: Reihe B: Geisteswissenschaften 5, Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag (1974).

- HENDRICKX 2013: S. Hendrickx, F. Förster, M. Eyckerman, The Pharaonic potery of the Abu Ballas Trail: ‘Filling stations’ along a desert highway in southwestern Egypt, in Desert Road Archaeology in Ancient Egypt and Beyond - Africa Praehistoria 27, Heinrich-Barth-Institut (2013).

- JACKSON 2002: R. B. Jackson, At Empire's Edge: Exploring Rome's Egyptian Frontier, Yale Univ. Press (2002).

- KAPER 2011: O. E. Kaper, Tempel an der "Rückseite der Oase" - Aktuelle Grabungen decken eine ganze Kulturlandscaft auf, Antike Welt 02/2011, Phillip von Zabern (2011), 15-19.

- KENDALL 2001: T. Kendall, Al-Meragh Discovery and General Description, Learning Sites, Inc (2001), .

- KENRICK 2013: P. Kenrick, Cyrenaica (Libya Archaeological Guides), Silphium Press (2013).

- KIRWAN 1972: P. Kirwan, An Ethiopian-Sudanese Frontier Zone in Ancient History, The Geographical Journal 138, No. 4 (1972), 457-465.

- KLEMM 2013: D. Klemm, R. Klemm, Gold and Gold Mining in Ancient Egypt and Nubia Geoarchaeology of the Ancient Gold Mining Sites in the Egyptian and Sudanese Eastern Deserts, Natural Science in Archaeology, Springer (2013).

- KUHLMANN 2007: K.P. Kuhlmann, Das Ammoneion – ein ägyptisches Orakel in der libyschen Wüste; in: G.Dreyer, D.Polz (Hrsg.), Begegnung mit der Vergangenheit. 100 Jahre in Ägypten. Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Kairo 1907-2007, Philip von Zabern (2007), 76-86.

- LASSÁNYI 2010: G. Lassányi, Tumulus burials and the nomadic population of the Eastern Desert in Late Antiquity, in W. Godlewski and A. Łajtar (eds), Between the Cataracts II, Warszawa, 595-606.

- LIVERANI 2005: M. Liverani (ed.), Aghram Nadharif. The Barkat Oasis (Sha 'abiya of Ghat, Libyan Sahara) in Garamantian Times, AZA Monographs Vol. 5. Florence: All'Insegna del Giglio (2005).

- LOEBEN 2011: C. E. Loeben, Ein Geschenk der Wüste - Oasen der Westwüste ägyptens und ihre archäologischen Schätze, Antike Welt 02/2011, Phillip von Zabern (2011), 8-14.

- LOHWASSER 2009-2014: A. Lohwasser, Report of the Survey in the Wadi Abu Dom - First - Fifth Season, Wadi Abu Dom Itinerary Project (2009-2014), .

- LOHWASSER 2014: A. Lohwasser, Kush and Her Neighbours beyond the Nile Valley, in J.R. Anderson, D.A. Welsby (ed.), The Fourth Cataract and Beyond. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference for Nubian Studies; British Museum Publications on Egypt and Sudan 1 (2014), 125-134.

- MARZOLI 2010: D. Marzoli, A. El Khayari, Vorbericht Mogador (Marokko) 2008, Madrider Mitteilungen, DAI Madrid (2010).

- MATTINGLY 1995: D. J. Mattingly, Tripolitania, University of Michigan Press (1995).

- MATTINGLY 2006: D. J. Mattingly, The Garamantes: the First Libyan State, in The Libyan Desert: Natural Resources and Cultural Heritage, Society for Libyan Studies Monograph number 6 (2006).

- MATTINGLY 2013a: D. J. Mattingly, M. Sterry, The first towns in the central Sahara, Antiquity Vol. 87 No. 336 (2013) 503–518.

- MATTINGLY 2013b: D. J. Mattingly, A. Rushworth, M. Sterry, V. Leitch, Frontiers of the Roman Empire: The African Frontiers, Society of Lybian Studies (2013).

- MONOD 1971: T. Monod, Le mythe de l'Émeraude des Garamantes, Antiquités africaines 8 (1974), 51-66.

- MORI 2010: L. Mori, Between the Sahara and the Mediterranean Coast: the Archaeological Research in the Oasis of Fewet (Fazzan, Libyan Sahara) and the Rediscovery of the Garamantes, Bolletini di Archeologia on line I Volume speciale A/A10/2 (2010).

- MORI 2013: L. Mori, Fortified Citadels and Castles in Garamantian Times: the Evidence from Southern Fazzan (Libyan Sahara), in F. Jesse & C. Vogel (eds.), The Power of Walls - Fortifications in Ancient Northeastern Africa, Heinrich-Barth-Institut e.V. (2013).

- PHILLIPSON 2012: D. W. Phillipson, Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC - Ad 1300, Boydell & Brewer (2012).

- PLEUGER 2019: E. Pleuger, J.-Ph. Goiran, I. Mazzini, H. Delile, A. Abichou, A. Gadhoum, H. Djerbi, N. Piotrowska, A. Wilson, E. Fentress, I. Ben Jerbania, N. Fagel, Palaeogeographical and palaeoenvironmental reconstruction of the Medjerda delta (Tunisia) during the Holocene, Quaternary Science Reviews 220 (2019,) 263-278.

- PICHLER 2005: W. Pichler, G. Negro, Giancarlo, The Libyco-Berber inscriptions in the Selima Oasis, Sahara Vol. 16 (2005), 173-178.

- VAN RENGAN 2011: W. Van Rengan, Written material from the Graeco-Roman period, in: D. Peacock, L. Blue (ed.), Myos Hormos – Quseir al-Qadim: Roman and Islamic ports on the Red Sea 2: Finds from the excavations 1999–2003, University of Southampton Series In Archaelogy No. 6 (2011), 335-338.

- SADR 1999: K. Sadr, A. Castiglioni, Deraheib: Die goldene Stadt der Nubischen Wüste, MittSAG 9 (1999), 52-57.

- SCHIMMER 2012: F. Schimmer, New evidence for a Roman fort and vicus at Mizda (Tripolitania), Libyan Studies Vol. 43 (2012), 33-39.

- SCHÖRNER 2000: H. Schörner, Künstliche Schiffahrtskanäle in der Antike - Der sogenannte antike Suez-Kanal, Skyllis 3.1 (2000), 28 – 43.

- SERNICOLA 2011: L. Sernicola, L. Phillipson, Aksum’s regional trade: new evidence from archaeological survey, Azania 46, No. 2 (2011), 190-204.

- SIDEBOTHAM 1991: S. E. Sidebotham, R. E. Zitterkopf, J. A. Riley, Survey of the 'Abu Sha'ar-Nile Road, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 95, No. 4 (1991), 571-622.

- SIDEBOTHAM 2000: S. E. Sidebotham, R. E. Zitterkopf, C. C. Helms, Survey of the Via Hadriana: The 1998 Season, Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, Vol. 37 (2000), 115-126.

- SIDEBOTHAM 2004: S. E. Sidebotham, G. T. Mikhail, J. A. Harrell, R. S. Bagnall, A Water Temple at Bir Abu Safa (Eastern Desert), Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt Vol. 41 (2004), 149-159.

- SWANSONS 1971: J. T. Swanson, The Myth of Trans-Saharan Trade during the Roman Era, The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 8, No. 4 (1975), 582-600.

- THOMAS 2012: R. I. Thomas, Port communities and the Erythraean Sea trade, British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan 18 (2012), 169–99.

- TOMBER 2012: R. Tomber, From the Roman Red Sea to beyond the Empire: Egyptian ports and their trading partners, British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan 18 (2012), 201–215.

- TÖRÖK 1999: L. Török, The Kingdom of Kush - Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization, Handbuch der Orientalistik Abt.2 Bd. 31 (1999).

- TROUSSET 1997: P. Trousset, Nouvelles barrières romaines de contrôle dans l'extrême sud tunisien, BCTH 24, (Afrique du Nord, 1997, 155-163.

- WILSON 2012: A. Wilson, Saharan trade in the Roman period: short-, medium- and long-distance trade networks, Azania, Vol. 47, No. 4 (2012), 409-449.

- WOZNIAK 2021: M. Woźniak, Lost port of the Red Sea, Academia Letters, Article 213: https://doi.org/10.20935/AL213.

- ZITTERKOPF 1989: R. E. Zitterkopf, S. E. Sidebotham, Stations and Towers on the Quseir-Nile Road, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 75 (1989), 155-189.

Middle East

- ALTWEEL 2004: M. R. Altweel, S. R. Hauser, Trade Routes to Hatra according to evidence from ancient sources and modern satellite imagery, Baghdader Mitteilungen 35 (2004), 59-86.

- BONACOSSI 2020, D. M. Bonacossi, Wo Alexander der Grosse Dareios Besiegte - Gaugamela, der Ursprung des Hellenismus, Antike Welt 04/2020, WBG Darmstadt (2020), 63-71.

- BOWERSOCK 1983: G. W. Bowersock, Roman Arabia, Harvard University Press (1983).

- BRETON 1999: J. F. Breton, Arabia Felix from the time of the Queen of Sheba: eighth century B.C. to first century A.D., University of Notre Dame Press (1999).

- EDWELL 2008: P. M. Edwell, Between Rome and Persia: The Middle Euphrates, Mesopotamia and Palmyra Under Roman Control, Routledge (2008).

- FELDBACHER 2022: R. Feldbacher, Netzwerk Seidenstraße, wbg Philipp von Zabern (2022).

- GRAJETZKI 2011: W. Grajetzki , Greeks and Parthians in Mesopotamia and beyond: 331 BC - 224 AD, Bristol Classical Press (2011).

- GREGORATTI 2009: L. Gregoratti, Hatra: On the West of the East, in Hatra Politics Culture and Religion between Parthia and Rome - Proceedings of the conference held at the University of Amsterdam 18-20 December 2009.

- HACKL 2010: U. Hackl, B. Jacobs, D. Weber (Hrsg.), Quellen zur Geschichte des Partherreiches. Textsammlung mit Übersetzungen und Kommentaren, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht (2010).

- HAUSLEITNER 2013: A. Hausleitner, Tayma - eine frühe Oasensiedlung, Archäologie in Deutschland, 3/2013, 14-19.

- HOYLAND 2001: R. G. Hoyland, Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam, Routledge Chapman & Hall (2001).

- JOTHERI 2016: J. Hamza Abdulhussein Jotheri, Holocene avulsion history of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers in the Mesopotamian Floodplain, Durham theses, Durham University (2016), http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11752/.

- KENNEDY 2004: D. Kennedy, The Roman Army in Jordan, Council for British Research in the Levant, 2nd Revised edition (2004).

- LIU 2015: S. Liu, Th. Rehren, E. Pernicka, A. Hausleiter, Copper processing in the oases of northwest Arabia: technology, alloys and provenance, Journal of Archaeological Science 53 (2015), 492-503.

- LUCIANI 2016: M. Luciani, Mobility, Contacts and the Definition of Culture(s) in New Archaeological Research in Northwest Arabia, in M. Luciani (ed.) The Archaeology of North Arabia, Oases and Landscapes, Oriental and European Archaeology Volume 4, Austrian Academy of Sciences Press (2016), 21-56.

- MILLAR 1995: F. Millar, The Roman Near East: 31 BC-AD 337, Carl Newell Jackson Lectures No. 6, Harvard University Press (1995).

- NEZAFATI 2008: N. Nezafati, M. Momenzadeh, E. Pernicka, New Insights into the Ancient Mining and Metallurgical Researches in Iran, in Ü. Yalçin, H. Özbal, A. G. Paşamehmetoğlu (eds.), Ancient Mining in Turkey and the Eastern Mediterranean, Atilim University (2008), 307-328.

- NEZAFATI 2012: N. Nezafati, E. Pernicka, Early Silver Production in Iran, Iranian Archaeology, No. 2 (2012).

- OATES 1956: D. Oates, The Roman Frontier in Northern Iraq, The Geographical Journal 122, No. 2 (1956), 190-199.

- PALERMO 2016: R. Palermo, Filling the Gap: The Upper Tigris Region from the Fall of Nineveh to the Sasanians. Archaeological and Historical Overview Through the Data of the Land of Nineveh Archaeological Project, in K. Kopanias, J. MacGinnis, Archaeological Research in the Kurdistan Region and Adjacent Areas, Archaeopress Archaeology (2016), 277-297.

- ROLL 1995: I. Roll, A Map of Roman Imperial Roads in the Land of Israel, the Negev and Transjordan, in Eilat – Studies in the Archaeology, History and Geography of Eilat the Arava, Israel Exploration Society (1995), 209.

- ROLL 2009: I. Roll, Between Damascus and Megido: Roads and Transportation in Antiquity Across the Northeastern Approaches to the Holy Land, in: L. Di Segni, Y. Hirschfeld, J. Patrich and R. Talgam (eds.), Man Near A Roman Arch – Studies presented to Prof. Yoram Tzafrir, Jerusalem (2009), 10.

- SPEIDEL M.A. 2007: M. A. Speidel, Ausserhalb des Reichs? - Zu neuen Inschriften aus Saudi Arabien und zur Ausdehnung der römsichen Herrschaft am Roten Meer, ZPE 163 (2007) 296-306.

- SPEIDEL M.A. 2007b: M. A. Speidel, Ein Bollwerk für Syrien - Septimius Severus und die Provinzordnung Nordmesopotamiens im dritten Jahrhundert, Chiron 37 (2007) 405–433.

- SPEIDEL M.P. 1987: M. P. Speidel, The Roman Road to Dumata (Jawf in Saudi Arabia) and the Frontier Strategy of "Praetensione Colligare", Historia Bd. 36, No. 2 (1987), 213-221.

- SCHIETTECATTE 2006: J. Schiettecatte, Villes et urbanisation de l’Arabie du Sud à l’époque préislamique : formation, fonctions et territorialités urbaines dans la dynamique de peuplement régionale, Histoire, Université Panthéon-Sorbonne - Paris I (2006), Français.

- SCHIETTECATTE 2007: J. Schiettecatte, Urbanization and Settlement pattern in Ancient Hadramawt (1st mill. BC), Bulletin of Archaeology of the Kanazawa University 28 (2007), 11-28.

- SCHUOL 2000: M. Schuol, Die Charakene - ein mesopotamisches Königreich in hellenistisch-parthischer Zeit, Steiner Franz (2000).

- SOMMER 2006: M. Sommer, Der römische Orient: Zwischen Mittelmeer und Tigris, Theiss Konrad (2006).

- STEIN 1940: A. Stein, Surveys on the Roman Frontier in Iraq and Trans-Jordan, The Geographical Journal, 95, No. 6 (1940), 428-438.

- STEIN 1940: A. Stein, Surveys on the Roman Frontier in Iraq and Trans-Jordan, The Geographical Journal, 95, No. 6 (1940), 428-438.

- THOMSEN 1917: P. Thomsen, Die römischen Meilensteine der Provinzen Syria, Arabia, und Palästina, Zeitchrift des Deutschen Palastina-Vereins 40 (1917), 1-103.

- TOURTET 2015: F. Tourtet, F. Weigel, \emph{Taymāʾ in the Nabataean kingdom and in "Provincia Arabia"}, in Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies Vol. 45, Papers from the forty-eighth meeting of the Seminar for Arabian Studies held at the British Museum, London, 25 to 27 July 2014, Archaeopress (2015), 385-404.

- TUBACH 1993: J. Tubach, Die Insel der Mesene, Die Welt des Orients, Bd. 24 (1993), 112-126.

- WEISS 2004: P. Weiß, M. P. Speidel, Das erste Militärdiplom für Arabia, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 150, (2004), 253-264.

- WALSTRA 2011: J. Walstra, V. M.A. Heyvaert, P. Verkinderen, Mapping Late Holocene Landscape Evolution and Human Impact – A Case Study from Lower Khuzestan (SW Iran), Developments in Earth Surface Processes Volume 15 (2011), 551-575.

- WEISS 2004: P. Weiß, M. P. Speidel, Das erste Militärdiplom für Arabia, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 150, (2004), 253-264.

- WILLEITNER 2013: J. Willeitner, Die Weihrauchstraße, Philipp von Zabern (2013).

- WIESEHÖFER 1998: J. Wiesehöfer (Hrsg.), Das Partherreich und seine Zeugnisse - The Arsacid-Empire: Sources and Documentation, Steiner Franz (1998).

- WHITCOMB 1987: D. Whitcomb, Bushire and the Angali Canal, Mesopotamia 12 (1987), 311-336.

Northwestern Europe

- BAATZ 2002: D. Baatz, F.-R. Herrmann, Die Römer in Hessen, Nikol (2002).

- BECHERT 2007: T. Bechert, Germania inferior. Eine Provinz an der Nordgrenze des Römischen Reiches, Orbis Provinciarum, Philipp von Zabern (2007).

- BLECKMANN 2002: B. Bleckmann, Die Alamannen im 3. Jahrhundert: althistorische Bemerkungen zur Ersterwähnung und zur Ethnogenese, Museum Helveticum 59.3 (2002).

- BOS 2011: British Ordnance Survey, Historical Map Roman Britain 1 : 625.000, 6th Revised edition, Ordnance Survey (2011).

- BOUET 2015: A. Bouet, Aquitanien in römischer Zeit, Philipp von Zabern (2015).

- CAMPOREALE 2003: G. Camporeale, Die Etrusker. Geschichte und Kultur, Artemis & Winkler (2003).

- FERDIERE 2011: A. Ferdière, Gallia Lugdunensis. Eine römische Provinz im Herzen Frankreichs, Philipp von Zabern (2011).

- FISCHER 2025: Th. Fischer, Die Markomannenkriege unter Marc Aurel, Antike Welt 4.25, Verlag Herder (2025).

- FREEMAN 2008: P. Freeman, Ireland and the Classical World, University of Texas Press (2008).

- GSCHLÖSSL 2006: R. Gschlößl, Im Schmelztiegel der Religionen: Göttertausch bei Kelten, Römern und Germanen, Philipp von Zabern (2006).

- GROS 2011: P. Gros, Gallia Narbonensis: Eine römische Provinz in Südfrankreich, Philipp von Zabern (2011).

- HOBBS 2011: R. Hobbs, Das römische Britannien, Wiss. Buchges. Darmstadt (2011).

- JONES 1980: G. D. B. Jones, The Roman Mines at Riotinto, Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 70 (1980), 146-165.

- KEMKES 2012: M. Kemkes, M. Scholz, Das Römerkastell Aalen. UNESCO-Welterbe, Theiss (2012).

- KLEE 2013: M. Klee, Germania Superior – Eine römische Provinz in Deutschland, Frankreich und der Schweiz, Friedrich Pustet (2013).

- KLEINEBERG 2010: A. Kleineberg, C. Marx, E. Knobloch, D. Lelgemann, Germania und die Insel Thule: Die Entschlüsselung von Ptolemaios' Atlas der Oikumene, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft Darmstadt (2010).

- LINDSMEIER 2006: K-D. Lindsmeier, Big Business in Hispanien, Abenteuer Archäologie 1 (2006), 40-45.

- MILLET 2000: M. Millett, The Romanization of Britain -an essay in archaeological interpretation, Reprinted Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press (2000).

- NEWIG 2004: J. Newig, Die Küstengestalt Nordfrieslands im Mittelalter nach historischen Quellen, in G. Schernewski und T. Dolch (Hrsg.): Geographie der Meere und Küste (2004).

- PANZRAM 2013: S. Panzram, Kleine Geschichte der Balearen, Klio - Beiträge zur Alten Geschichte 95, 1 (2013), 5–39.

- PLANCK 2005: D. Planck (ed.), Die Römer in Baden-Württemberg, Theiss (2005).

- POHL 2004: W. Pohl, Die Germanen, Oldenbourgs Enzyklopädie der deutschen Geschichte Bd. 57, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2. Auflage (2004)

- RICKARD 1928: T. A. Rickard, The Mining of the Romans in Spain, Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 18 (1928), 129-143.

- ROLDAN-HERVAS 2001: J. M. Roldán Hervás, Historia antigua de España I. Iberia prerromana, Hispania republicana y alto imperial, Universidad Nacional De Educación a Distancia (2001).

- SCHALLMAYER 2010: E. Schallmayer, Der Odenwaldlimes: Entlang der römischen Grenze zwischen Main und Neckar, Theiss (2010).

- SCHMIDTS: T. Schmidts, Zentralorte in der Provinz Raetien, Online Publikation des RGZM im Rahmen des Projektes Transformation - The Emergence of a Common Culture in the Northern Provinces of the Roman Empire from Britain to the Black Sea up to 212 A.D., rgzm.de/transformation.

- STEIDL 2016: B. Steidl et Al., Römer und Germanen am Main: Ausgewählte archäologische Studien, LOGO VERLAG Eric Erfurth (2016).

- TARPIN 1999: M. Tarpin, Colonia, Municipium, Vicus: Institutionen und Stadtformen, in Colonia - municipium - vicus. Struktur und Entwicklung städtischer Siedlungen in Noricum, Rätien und Obergermanien Beiträge der Arbeitsgemeinschaft ‘Römische Archäologie’ bei der Tagung des West- und Süddeutschen Verbandes der Altertumsforschung in Wien 21.-23.5.1997, British Archaeological Report, International Series 783 (1999).

- TOL 2014: G. Tol, T. de Haas, K. Armstrong, P. Attema MINOR CENTRES IN THE PONTINE PLAIN: THE CASES OF FORUM APPII AND AD MEDIAS, Papers of the British School at Rome 82 (2014), 109–134.

- WACHER 1997: J.S. Wacher, The Towns of Roman Britain, Routledge Chapman & Hall (1997).

- WIGHTMAN 1985: E. Wightman, Gallia Belgica, University of California Press, Berkeley (1985).

- WOLTERS 2011: R. Wolters, Die Römer in Germanien, C.H.Beck, 6. Auflage (2011).

Eastern Europe and Asia Minor

- ACRUDOAE 2012: I. Acrudoae, Ala I Pannoniorum Tampiana: history and mobility, Classica et Christiana, 7/1 (2012), 9-16.

- ARTHUR 1901: J. Arthur R. Munro, Roads in Pontus, Royal and Roman, The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 21 (1901), 52-66.

- BORHY 2014: L. Borhy, Die Römer in Ungarn, Phillip von Zabern (2014).

- BRANDT 2005: H. Brandt, F. Kolb, Lycia et Pamphylia. Eine römische Provinz im Südwesten Kleinasiens, Philipp von Zabern, Mainz (2005).

- BRZEZINSKI 2002: R. Brzezinski, M. Mielczarek, The Sarmatians 600 BC - AD 450, Osprey Publishing, (2002).

- BUJSKICH 2006: S. B. Bujskich, Die Chora des pontischen Olbia: Die Hauptetappen der räumlich-strukturellen Entwicklung, in Black Sea Studies 4, Aarhus University Press (2006), 115-140.

- BÜLOW 2008: G. von Bülow, R. Ivanov, Thracia: Eine römische Provinz auf der Balkanhalbinsel, Philipp von Zabern (2008).

- BURNEY 1971: C. Burney, D. Marshall Lang, The Peoples of the Hills: Ancient Ararat and Caucasus, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, (1971).

- CHANIOTIS 2014: A. Chaniotis, Das antike Kreta, C.H.Beck, 2. Auflage (2014).

- ERCIYAS 2001: D. Burcu Arıkan Erciyas, Studies in the archaeology of hellenistic Pontus, PhD Thesis, University of Cincinnati (2001).

- FISCHER 2002: T. Fischer, Noricum, Philipp von Zabern (2002).

- FORNASIER 2002: J. Fornasier Hrsg., Das Bosporanische Reich. Der Nordosten des Schwarzen Meeres in der Antike, Philipp von Zabern (2002).

- GAJUKEVIČ 1971: V. F. Gajdukevič, Das Bosporanische Reich, 2. erweiterte Auflage, Akademie-Verlag (1971).

- GREGORATTI 2013: L. Gregoratti, The Caucasus: a Communication Space between Nomads and Sedentaries (1st BC-2nd AD), in S. Magnani, Mountain Areas as Frontiers and/or Interaction and Connectivity Spaces, Arachne (2013), 477-493.

- GUDEA 2006: N. Gudea, T. Lobüscher, Dacia: Eine römische Provinz zwischen Karpaten und Schwarzem Meer, Philipp von Zabern (2006).

- KAKHIDZE 2008: E. Kakhidze, Apsaros: A Roman Fort in Southwestern Georgia, in Black Sea Studies 8, Aarhus University Press (2008), 303-332.

- KOVACS 2003: P. Kovács , Mogetiana und sein Territorium, Pannonica Provincialia et Archaeologia. Eugenio Fitz octogenario, Libelli Archaeologici I (2003), 277-306.

- KRYZICKIJ 2006: S. D. Kryzickij, The Rural Environs of Olbia: Some Problems of Current Importance, in Black Sea Studies 4, Aarhus University Press (2006), 99-114.

- MATEI-POPESCU 2016: F. Matei-Popescu, O. Tentea, The Eastern Frontier of Dacia. A Gazetteer of the Forts and Units, in V. Bârcă (ed.), Orbis Romanus and Barbaricum - The Barbarians around the Province of Dacia and Their Relations with the Roman Empire, Mega Publishing House (2016), 7-24.

- MAREK 2003: C. Marek, Pontus et Bithynia. Die römischen Provinzen im Norden Kleinasiens, Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2003.

- MAREK 2010: C. Marek, P. Frei, Geschichte Kleinasiens in der Antike, 2. durchges. Aufl., C.H. Beck (2010).

- MARTHA 2006: W. Martha, B. Bowsky, V. Niniou-Kindeli, On the Road Again: A Trajanic Milestone and the Road Connections of Aptera, Hesperia 75 (2006), 405-433.

- MIRKOVIC 2007: M. Mirkovic, Moesia Superior: Eine Provinz an der mittleren Donau, Philipp von Zabern (2007).

- MITCHELL 1999: S. Mitchell, Administration of Roman Asia from 133 BC to 250 AD, in W. Eck (Hrsg.) Lokale Autonomie und Ordnungsmacht in den kaiserzeitlichen Provinzen vom 1. bis 3. Jahrhundert, Schriften des Historischen Kollegs 42, Oldenbourg (1999), 17-46.

- MORENO 2008: A. Moreno, HIERON - The Ancient Sanctuary at the Mouth of the Black Sea, Hesperia 77 (2OO8), 655-709.

- NEMETH 2011: E. Nemeth, F. Fodorean, D. Matei, D. Blaga, Der südwestliche Limes des römischen Dakien. Strukturen und Landschaft, Editura Mega (2011).

- NEMETH 2016: E. Nemeth, Dies- und jenseits der Südwestgrenze des römischen Dakien. Neuere Forschungsergebnisse, in A. Rubel (Hg.), Die Barbaren Roms - Inklusion, Exklusion und Identität im Römischen Reich und im Barbaricum (1.-3. Jahrhundert n. Chr.), Hartung-Gorre Verlag (2016), 97-115.

- NOVICENKOVA 2008: N. G. Novicenkova, Mountainous Crimea: A Frontier Zone of Ancient Civilization, in Black Sea Studies 8, Aarhus University Press (2008), 287-302.

- OLTEAN 2007: I. A. Oltean, Dacia: Landscape, Colonization and Romanization, Routledge (2007).

- OCHOTNIKOV 2006: S. B. Ochotnikov, The Chorai of the Ancient Cities in the Lower Dniester Area (6th Century BC-3rd Century AD), in Black Sea Studies 4, Aarhus University Press (2006), 81-98.

- ÖZTÜRK 2022: S. N. Öztürk, Sarikaya - Eine kaiserzeitliche Thermalbadeanlage un Kappadokien, Antike Welt 05/2022, WBG Darmstadt (2022), 68-76.

- PATARLI 2007: M. Pazarli, E. Livieratos, C. Boutoura, Road network of Crete in Tabula Peutingeriana, e-Perimetron 2, No. 4 (2007), 245-260.

- PIETA 1982: K. Pieta, Die Púchov Kultur, Archäologisches Institut der Slowakischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Nitra (19982).

- SANADER 2007: M. Sanader (Hrsg.), Kroatien in der Antike, Philipp von Zabern (2007).

- SANADER 2009: M. Sanader, Dalmatia: Eine römische Provinz an der Adria, Philipp von Zabern (2009).

- Сарновски 2004: Сарновски Т., Ковалевская Л.А., защите Херсонесского государства союзным римским военным контингентом - On the defence of tauric Chersonesos by the Roman allies, Российская археология No. 2 (2004), 40-50.

- SCHOLLMEYER 2009: P. Schollmeyer, Das antike Zypern: Aphrodites Insel zwischen Orient und Okzident, von Zabern (2009).

- STROBEL 1988: K. Strobel, Zu den Auszeichnungen der Ala I Flavia Augusta Britannica milliaria c.R. bis torquata ob virtutem, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 73 (1988), 176–180.

- SZABO 2014: C. Szabó, The map of Roman Dacia in the recent studies, Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology (JAHA) nr.I, Cluj - Napoca (2014), 44-51.

- TEMPORINI 1980: H. Temporini [hrsg.], Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II. Principat - Politische Geschichte: Provinzen u. Randvölker, griech. Balkanraum, Kleinasien, ANRW II. Band 7.2 (1980).

- TENTEA 2004: O. Tentea, M. Popescu, Alae et cohortes Daciae et Mosiae. A review and updating of J.Spaul’s Ala 2 and Cohors 2, Acta Musei Napocensis 39-40/1 2002-2003 (2004), 259–296.

- TEODOR 2015: E. S. Teodor, The Invisible Giant: Limes Transalutanus, Editura Cetatea de Scaun (2015).

- TÜRK 2020: M. Türk, Hadrianutherai - Eine noch nicht lokalisierte Stadt der römsichen Kaiserzeit in Asia Minor, Antike Welt 06/2020, WBG Darmstadt (2020), 63-66.

- VAJDA 2014: T. Vajda, Adatok és észrevételek a Balaton 3–15. század közötti vízállásához, Belvedere Meridionale XXVI. 3 (2014), 49–62.

- VALEVA 2015: J. Valeva, E. Nankov, D. Graninger (eds.), A Companion to Ancient Thrace, Wiley-Blackwell (2020).

- VITALE 2013: M. Vitale, Kolchis in der Hohen Kaiserzeit: Römische Eparchie oder nördlicher Aussenposten des Limes Ponticus?, Historia 62, No. 2 (2013), 241-258.

- ZAHRNT 2010: M. Zahrnt, Die Römer im Land Alexander des Großen, Philipp von Zabern, (2010).